Black Scoter

General Description

Black Scoters are large, mostly black or dark gray sea ducks. Formerly called the Common Scoter, the Black Scoter is the least common of the three scoters. Adult males are solid black with a bulbous yellow knob on an otherwise black bill. Females and juveniles are dark gray, lighter on the cheek with a dark cap. Their bills are dark and lack the knob found in adult males.

Habitat

The breeding range of the Black Scoter is at the edge of the northern forest or in the treeless tundra, where they breed on small, shallow lakes, ponds, sloughs, and river banks with tall grasses to conceal nests. In winter, they can be found on coastal bays and along coastlines, usually in shallow water within a mile of shore.

Behavior

Scoters spend the non-breeding part of the year in large flocks on the ocean. Black Scoters forage by diving and swimming under water, propelled by their feet. They usually feed in areas of open water, avoiding dense submergent or emergent vegetation. They swallow their prey under water, unless it is large or bulky. They are strong fliers, but must get a running start on the water to get airborne.

Diet

At sea, mollusks are the most common prey item of the Black Scoter, although crustaceans and other aquatic invertebrates are also part of the diet. On fresh water, aquatic insects, fish eggs, mollusks, small fish, and some plant matter are eaten.

Nesting

Most females probably start breeding at the age of two. Pairs form in late fall and winter. The female builds the nest on the ground, usually near the water on a hummock or ridge, well concealed by vegetation. The nest is a shallow depression lined with plant material and down. The female lays 8 to 9 eggs and incubates them for 27 to 31 days. The pair bond dissolves, and the male departs for the molting grounds soon after the female begins incubation. It is not known whether pairs re-form in the fall, or if new pairs are formed. Shortly after hatching, the young leave the nest and head to the water. The female tends the young and continues to brood them at night, but they can swim and feed themselves. Most females abandon their broods after one to three weeks. Multiple broods gather together on lakes until they can fly, at 6 to 7 weeks.

Migration Status

Black Scoters migrate north from March through May and south from late September through November. The fall migration is preceded by a molt migration where birds molt in large groups at northern coastal sites before heading south in fresh plumage.

Conservation Status

Although the Black Scoter is by some accounts the least numerous of the scoters in North America, numbers appear to be stable. Other sources document a long-term trend of decline. Many surveys of scoters do not differentiate between the three species, and it is difficult to determine the population trends of each species independently. The two most significant potential threats to Black Scoters in Washington are oil spills and heavy-metal contamination (which accumulates in prey items such as mussels).

When and Where to Find in Washington

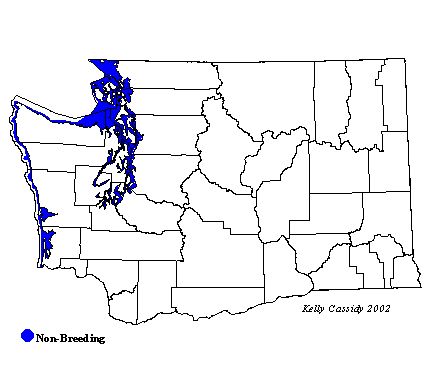

Some of the major wintering areas of Black Scoters in the West include the coastal waters off Washington, where they are widespread but not common from mid-November to mid-May. Limited numbers can also be found in the Strait of Juan de Fuca and Puget Sound. They are regularly seen at Budd Inlet in the Olympia Harbor (Thurston County) and in Penn Cove on Whidbey Island (Island County).

Abundance

Abundance

| Ecoregion | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oceanic | ||||||||||||

| Pacific Northwest Coast | U | U | U | U | U | R | U | U | U | U | ||

| Puget Trough | U | U | U | U | U | R | R | U | U | U | U | |

| North Cascades | ||||||||||||

| West Cascades | ||||||||||||

| East Cascades | ||||||||||||

| Okanogan | ||||||||||||

| Canadian Rockies | ||||||||||||

| Blue Mountains | ||||||||||||

| Columbia Plateau |

Washington Range Map

North American Range Map

Family Members

Fulvous Whistling-DuckDendrocygna bicolor

Fulvous Whistling-DuckDendrocygna bicolor Taiga Bean-GooseAnser fabalis

Taiga Bean-GooseAnser fabalis Greater White-fronted GooseAnser albifrons

Greater White-fronted GooseAnser albifrons Emperor GooseChen canagica

Emperor GooseChen canagica Snow GooseChen caerulescens

Snow GooseChen caerulescens Ross's GooseChen rossii

Ross's GooseChen rossii BrantBranta bernicla

BrantBranta bernicla Cackling GooseBranta hutchinsii

Cackling GooseBranta hutchinsii Canada GooseBranta canadensis

Canada GooseBranta canadensis Mute SwanCygnus olor

Mute SwanCygnus olor Trumpeter SwanCygnus buccinator

Trumpeter SwanCygnus buccinator Tundra SwanCygnus columbianus

Tundra SwanCygnus columbianus Wood DuckAix sponsa

Wood DuckAix sponsa GadwallAnas strepera

GadwallAnas strepera Falcated DuckAnas falcata

Falcated DuckAnas falcata Eurasian WigeonAnas penelope

Eurasian WigeonAnas penelope American WigeonAnas americana

American WigeonAnas americana American Black DuckAnas rubripes

American Black DuckAnas rubripes MallardAnas platyrhynchos

MallardAnas platyrhynchos Blue-winged TealAnas discors

Blue-winged TealAnas discors Cinnamon TealAnas cyanoptera

Cinnamon TealAnas cyanoptera Northern ShovelerAnas clypeata

Northern ShovelerAnas clypeata Northern PintailAnas acuta

Northern PintailAnas acuta GarganeyAnas querquedula

GarganeyAnas querquedula Baikal TealAnas formosa

Baikal TealAnas formosa Green-winged TealAnas crecca

Green-winged TealAnas crecca CanvasbackAythya valisineria

CanvasbackAythya valisineria RedheadAythya americana

RedheadAythya americana Ring-necked DuckAythya collaris

Ring-necked DuckAythya collaris Tufted DuckAythya fuligula

Tufted DuckAythya fuligula Greater ScaupAythya marila

Greater ScaupAythya marila Lesser ScaupAythya affinis

Lesser ScaupAythya affinis Steller's EiderPolysticta stelleri

Steller's EiderPolysticta stelleri King EiderSomateria spectabilis

King EiderSomateria spectabilis Common EiderSomateria mollissima

Common EiderSomateria mollissima Harlequin DuckHistrionicus histrionicus

Harlequin DuckHistrionicus histrionicus Surf ScoterMelanitta perspicillata

Surf ScoterMelanitta perspicillata White-winged ScoterMelanitta fusca

White-winged ScoterMelanitta fusca Black ScoterMelanitta nigra

Black ScoterMelanitta nigra Long-tailed DuckClangula hyemalis

Long-tailed DuckClangula hyemalis BuffleheadBucephala albeola

BuffleheadBucephala albeola Common GoldeneyeBucephala clangula

Common GoldeneyeBucephala clangula Barrow's GoldeneyeBucephala islandica

Barrow's GoldeneyeBucephala islandica SmewMergellus albellus

SmewMergellus albellus Hooded MerganserLophodytes cucullatus

Hooded MerganserLophodytes cucullatus Common MerganserMergus merganser

Common MerganserMergus merganser Red-breasted MerganserMergus serrator

Red-breasted MerganserMergus serrator Ruddy DuckOxyura jamaicensis

Ruddy DuckOxyura jamaicensis